What Need to Know a Parent of Child with Hip Dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia is a disorder in which the ball of one of your thigh bones is not entirely covered by the hip socket. Your hip is your body’s largest ball-and-socket joint.

The hip joint is formed by the ball of your thigh bone (femoral head) fitting into the socket of your pelvis. If the hip is properly aligned, the ball rotates easily in the socket, allowing you to move.

However, if you have dysplasia, your hip joint is more likely to dislocate and wear out faster than usual. Consider a car with an out-of-balance tyre. That tire’s tread will wear out more quickly than if it were correctly positioned.

Hip dysplasia is a condition that most people are born with (this is called developmental dysplasia or congenital dislocation of the hip). Doctors normally check for it in newborns and at each well-baby visit until the child reaches the age of one year.

What is Hip Dysplasia in development?

A problem with the way a baby’s hip joint forms is known as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). The problem might begin before the baby is born, or it can develop after the baby is delivered and as the child grows. It can affect either one or both hips. Most DDH-affected infants grow up to be active, healthy children with no hip problems.

What happens when you have developmental dysplasia in your hip?

The top of the thighbone (the ball portion of the hip) fits into a socket in the pelvic bone. The ball moves in a variety of directions, yet it never leaves the socket. This allows us to move our hips forward, backward, and to the side. It also helps us walk and run by supporting our body weight.

The hip does not form properly in DDH. The ball portion of the joint may be out of the socket or only partially out of the socket. The ball component of the socket may occasionally slip in and out. The socket is frequently shallow. The hip joint will not grow properly if this is not corrected. This might result in hip arthritis and pain when walking at an early age.

Hip Dysplasia Symptoms

Hip dysplasia might have different indications and symptoms depending on your age. When children first begin walking, they may have one leg that is longer than the other, and one hip that is less flexible than the other or lame.

- The hips of the infant generate a popping or clicking sound that can be heard or felt.

- The legs of the newborn are not the same length.

- One hip or leg moves differently than the other.

- The skin folds beneath the buttocks and on the thighs do not match.

- When the youngster first begins to walk, he or she walks with a limp.

Hip pain or a limp may be the first indicators you notice as a teenager or young adult. You may also experience clicking or popping in the joint, but these are all signs of different hip problems.

The pain is commonly felt in the front of the groin and occurs when you engage in athletic activities. However, you may get pain in the side or back of your hip. It could start out moderate and only occurs once in a while, then get more intense and frequent over time. Half of the hip dysplasia patients have nighttime pain.

A minor limp may result from the pain. If you do have weak muscles, a bone deformity, or limited hip joint flexibility, you may develop a limp. You will not feel pain if you feel like you have a limp for one of those reasons.

Who is Affected by Hip Developmental Dysplasia?

DDH can affect any infant. However, babies who: are girls; are first-born babies; were breech babies (in the womb buttocks-down instead of head-down), especially during the third trimester of pregnancy; have a family member with the condition, such as a parent or sibling; etc.

DDH is a rare condition in which a baby is not born with it but develops after delivery. Swaddle a newborn’s hips and legs tightly together to avoid DDH in newborns who are not born with it. Make sure a baby’s legs have plenty of room to move about.

Causes and Risk Factors for Hip Dysplasia

Hip dysplasia is more common in females than in boys and can run in families. Because the hip joint is comprised of mushy cartilage when you are born, it shows up in babies. It hardens into bone over time.

During this time, the ball and socket assist mold one another, so if the ball does not fit properly into the socket, the socket may end up being too shallow and not fully form over the ball. This can happen for a variety of reasons just before a baby is born:

- It is the mother’s first time carrying a child.

- The baby is in the breech position, which means the back of the infant is facing the birth canal rather than the head.

- The infant is quite enormous. Or there’s oligohydramnios, a condition in which the baby’s movement is restricted due to a lack of amniotic fluid in the sac where the baby has lived during the pregnancy.

All these factors can lower the amount of space available in the womb, making things more crowded for the baby and shifting the ball out of its correct position. Swaddling babies with straight hips and knees might also exacerbate the problem.

Infants and small children

- Children that are treated with a cast may take a little longer to walk than predicted, but they should catch up after the cast is removed.

- It is possible that the leg length disparity will persist.

- It is possible that the hip socket is not as deep as it should be, necessitating surgery later in life.

Young adults and teenagers

- Hip dysplasia might result in one of two painful complications.

- Hip osteoarthritis is a type of arthritis that affects the joints of the hip.

- A labral tear is a tear in the cartilage that helps in keeping your hip solid.

Treatment

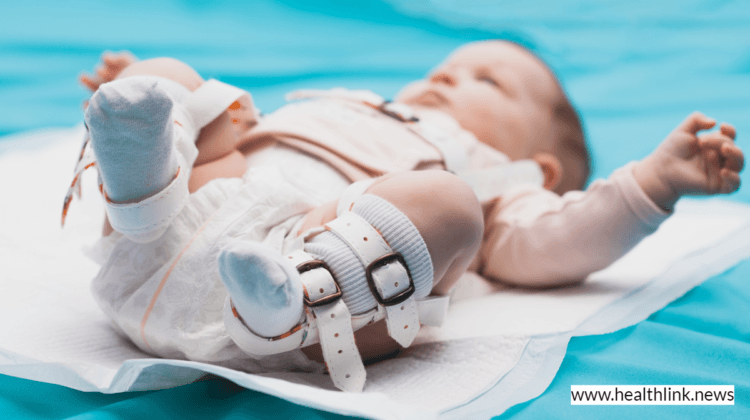

Hip dysplasia in infants is treated with a soft brace.

Treatment for hip dysplasia is determined by the patient’s age and the severity of the hip injury. For several months, infants are commonly treated with a soft brace, such as a Pavlik harness, which keeps the ball component of the joint firmly in its socket. This aids the socket in molding to the ball’s shape.

For babies older than 6 months, the brace is less effective. Instead, the doctor may reposition the bones into the right position and then use a full body cast to keep them there for several months.

Getting ready for your appointment

Your primary care physician will be the first to hear about your issues. He or she may recommend that you see an orthopedic surgeon.

What you can do in order to help?

You might want to do the following before your appointment:

- Make a list of any indications and symptoms you are having, even if they do not seem to be relevant to the reason you made the visit.

- Make a note of all the medications, vitamins, and supplements you are currently taking.

- Take a family member or a friend with you. It is sometimes tough to recall all the information given during a visit. Someone who is with you may recall something you overlooked or forgot.

- If you are changing doctors, ask for a copy of your past medical records to be sent to your new doctor.

- Make a list of questions to ask the doctor.

Because your time with the doctor is limited, preparing a list of questions ahead of time will help you make the most of it. The following are some basic questions to ask your doctor:

- Which of the following is the source of my symptoms?

- What types of exams do I require? Is there anything I should know about these tests before I take them?

- What treatments are available, and which ones would you suggest?

- What kind of adverse effects might I expect because of the treatment?

- Are there any alternatives to the major strategy you propose?

- Other health issues plague me. What is the best way for me to handle these conditions together?

- Is there any written information or brochures that I can take home with me?

- Can you recommend any websites where I could learn more about my condition?

In addition to the questions, you have prepared to ask your doctor, if you do not understand something, do not be afraid to ask questions during your session.